What Ultimate and the Declaration of Independence Teach Us About Leading Teams

The High Stakes of the Invisible Referee

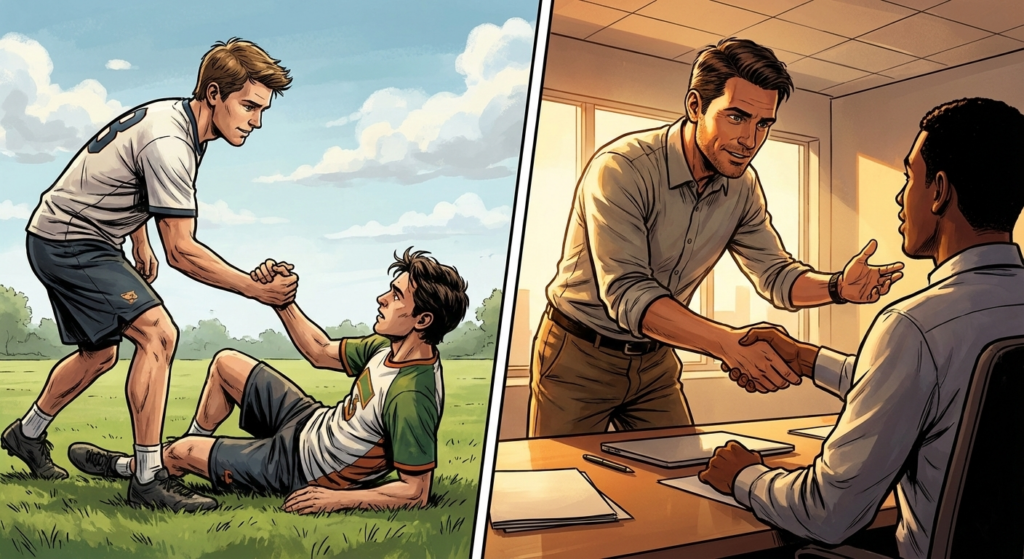

The sun is low over the field, the grass is slick with a late-afternoon dew, and the score is tied at game-point. In this moment, heart rates are red-lining, and the physical intensity is indistinguishable from any other elite sport. A player leaps for a disc, there is a tangle of limbs, and both athletes hit the turf. In most arenas, this is where the external authority steps in. A whistle blows, a yellow card is brandished, and a third-party judge determines who was the aggressor and who was the victim.

But in the world of Ultimate, there is no whistle.

At the elite level, including the World Championships where I have stood on the sand representing my country, the game is governed by a concept called Spirit of the Game. It is a radical social contract that places the responsibility for fair play entirely on the shoulders of the competitors. It is not merely a suggestion to “be nice”; it is a functional requirement for the game to exist. If the players cannot agree on the facts, the game cannot proceed.

At the very center of this practice is a cognitive leap that feels counter-intuitive to our competitive instincts: the foundational assumption that the other party did not intend to foul you.

When you are lying in the dirt, bruised and breathless, your lizard brain screams that you were wronged by a villain. It tells you that the person across from you is a cheater who valued a point more than your safety. But the social contract of the sport demands that you ignore that impulse. You must begin the conversation from the premise that your opponent was trying their best to play within the rules, and that the contact was an unfortunate byproduct of two people pursuing the same goal in the same space.

This is the “Spirit of the Game” in action. By choosing to believe in the integrity of the opponent, you bypass the cycle of retaliation and grievance. You move directly to resolution. It is a form of strategic optimism that allows a high-stakes system to function without a police force. And as I’ve learned over twenty years of leading teams in the corporate world, it is perhaps the most effective way to architect a reality that actually works.

The Architecture of Self-Evident Truths

This shift in perspective—choosing to believe in the best intentions of a competitor—is not an act of blind faith. It is a deliberate framing of reality. It mirrors one of the most famous lines in political history: “We hold these truths to be self-evident.” When those words were written, the authors weren’t making a scientific observation. They knew perfectly well that the “truths” they were proposing were not universally accepted, nor were they physically obvious in a world of monarchies and rigid hierarchies. Instead, they were performing an act of social engineering. They were saying, we are choosing to accept these things as true so that we can build a system that functions.

In management, we often make the mistake of waiting for “the truth” to reveal itself before we commit to a strategy. We wait to see if an employee is “actually” a high performer or “actually” trustworthy before we give them the keys to a project. But the most effective leaders understand that the baseline reality of a team is something you negotiate at the start, not something you discover at the end.

When I manage a team, I apply my own version of this self-evident truth: I assume that everyone gets out of bed in the morning wanting to do a good job. I operate from the premise that no one wakes up and says, “Today, I’m going to be the villain of the office; I’m going to miss my deadlines and let my colleagues down.” People are the heroes of their own stories, and in those stories, they are almost always trying their best with the tools and the context they have available to them.

This is where the psychology of the “Pygmalion Effect” takes hold. When a leader “hallucinates” a better version of their team, the team tends to rise to meet that hallucination. If I approach a struggling employee not as a problem to be solved, but as a capable person who is currently blocked by an obstacle, the entire nature of our interaction changes. I am no longer a judge handing down a sentence; I am a partner helping to clear the path. By assuming they want to succeed, I give them the psychological safety to admit where they are failing, which is the only way we can actually fix the root cause.

By framing our professional relationships around these “self-evident” positive intentions, we create a baseline of trust that allows us to move at the speed of the game. Just as on the Ultimate field, if we don’t have to spend our energy litigating each other’s character, we can spend all of our energy solving the problem at hand.

The Invisible Hand of Prosocial Logic

The critics of this approach often call it “naive.” They argue that if you assume the best of everyone, you simply open yourself up to being exploited by the few who truly are acting in bad faith. But this critique ignores the fundamental mechanics of human social capital. It fails to account for the “Invisible Hand” that guides our behavior within a community. We often associate Adam Smith’s famous concept with the cold calculation of the marketplace—the idea that individuals pursuing their own profit inadvertently benefit society. However, when applied to human relationships and team dynamics, the logic remains the same, though the currency changes.

In a social system, it is fundamentally rational to be “good.” Most people have a deep-seated, evolutionary drive to be seen as competent, reliable, and valuable members of their tribe. Their self-interest is inextricably linked to their reputation. When you provide a framework that assumes they are already that “best version” of themselves, you aren’t just being kind; you are lowering the barrier to entry for their most productive behaviors. You are making it easy for them to fulfill their own rational desire to succeed and belong.

This connects to a principle in game theory known as “Generous Tit-for-Tat.” In a world of rigid rules and immediate punishment, a single mistake can trigger a “death spiral” of mutual suspicion and retaliation—the workplace equivalent of a game-ending foul dispute. But by introducing a margin of “generosity”—by assuming the foul was an accident or the missed deadline was a resource issue—you prevent that spiral from ever starting. You maintain the cooperation loop.

We are, by and large, a pro-social species. We want to fit in, we want to be productive, and we want to be the hero who helps the team win. When a leader or a teammate leans into the “Spirit of the Game,” they are simply aligning the team’s goals with the individual’s natural psychological incentives. We are creating a marketplace where “good faith” is the most efficient way to operate.

In the end, the “self-evident truths” we choose to believe about one another become the architecture of the world we inhabit. If we build our teams on the assumption of malice or incompetence, we will spend our lives acting as referees, blowing whistles at every tangle of limbs. But if we choose to assume that the person across from us is trying their best to play fair, we get to stop litigating the past and start playing the game. We find that when we stop looking for villains, they tend to disappear—not because they were never there, but because we finally gave them a reason to be something else.