The Thirsty Monster in the Machine

If you’ve spent any time on the internet lately, you’ve likely encountered the concept of the water-guzzling AI. It is a compelling, almost Dickensian narrative: every time you ask a generative model to create a picture of a cat being an astronaut, you are effectively snatching a bottle of water out of the hands of a parched future generation. The headlines are visceral, claiming that data centers are draining our reservoirs and wasting precious resources to fuel our digital whims. It’s a powerful image, one that makes the act of creation feel like an act of environmental vandalism. But as with most things in the realm of high-stakes technology, the truth is less about a drain being pulled and more about a cycle being managed.

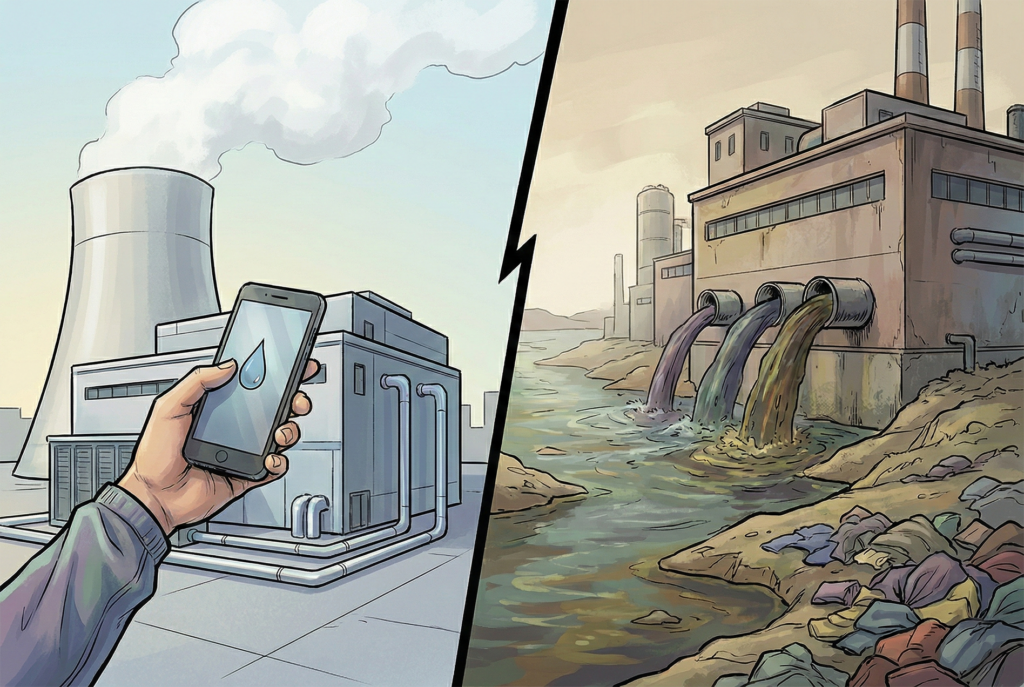

To understand why the water waste argument is often a case of missing the forest for the trees, we have to look at how a modern data center actually breathes. High-performance GPUs generate an immense amount of heat, and that heat has to go somewhere. The most efficient way to move it is through water. However, the narrative of waste implies a linear journey—water goes in, gets ruined, and disappears. In reality, modern, high-tier facilities are transitioning to closed-loop or evaporative cooling systems. In these setups, water acts as a courier, not a consumable. It carries heat away from the processors to a cooling tower where it evaporates, or it is chilled and recirculated indefinitely. While some water is lost to the atmosphere through evaporation, it remains firmly within the local hydrologic cycle. It becomes clouds; it becomes rain. It is used, certainly, but it is not destroyed.

Furthermore, we must move past the idea that AI is a luxury of the bored. This technology isn’t just a bystander in the climate crisis; it is one of our most effective tools for solving it. We are currently using AI to optimize renewable energy grids, design more efficient solar cells, and manage the incredibly complex supply chains that define our modern world. In this context, the energy and water used to power a data center aren’t just costs—they are investments in the high-speed calculations required to decarbonize our planet. Even if we want to focus on luxury uses, we can not ignore other digital habits. An hour of intensive online gaming on a high-end console or PC consumes roughly 0.2kWh of electricity—enough energy to power approximately 70 AI image generations. From a hardware perspective, generating an image is essentially just ten seconds of gaming-level GPU utilization. Yet, we rarely see headlines decrying the water used to cool the servers for a first-person shooter or a 4K movie stream. AI is being singled out not because of its unique consumption, but because of its novelty.

This digital thirst feels particularly egregious to critics because it is categorized as a luxury. Yet, we rarely apply this same scrutiny to the optional things we can physically touch. Consider the humble cotton t-shirt or the ubiquitous pair of denim jeans. To produce a single kilogram of cotton—roughly the amount needed for one outfit—requires upwards of 10,000 to 20,000 liters of water. Unlike the data center, where the water is largely a heat-transfer medium, the textile industry’s relationship with water is one of deep, often irreversible contamination. In global manufacturing hubs, the water used to dye fast fashion is frequently discharged back into local ecosystems laden with heavy metals, salts, and synthetic chemicals. This is water that is truly wasted because it is rendered toxic for humans, animals, and agriculture for decades.

The disparity in our outrage reveals a strange quirk in modern ethics: we are far more likely to condemn a transparent, digital process than a murky, physical one. We see the data center as a newcomer, an interloper in our environment, while we accept the catastrophic water footprint of a fifteen-dollar polyester blouse as a background fact of life. When we weigh the cost of an AI-generated image against the cost of a physical product, we have to ask ourselves which is the greater environmental sin: a tool that moves heat around a closed loop to solve complex engineering problems, or an industry that poisons the very rivers it draws from to produce a garment that will likely end up in a landfill within eighteen months.

The data center isn’t a monster drinking the world dry; it’s an incredibly efficient machine operating under a microscope. If we are going to talk about the ethics of water, we need to stop looking at the steam rising from a cooling tower and start looking at the colored sludge flowing out of a textile mill. One is a part of a cycle; the other is the end of it.

The Plastic Straw Paradox: Hidden Oil in Your Closet

The modern environmental movement has a peculiar obsession with symbols. We have collectively decided that the plastic straw is the ultimate emblem of ecological negligence—a thin, polypropylene tube of pure evil. We carry titanium replacements and struggle through soggy paper alternatives, all while feeling a righteous surge of doing our part. Yet, if you look at the person most vociferously arguing against the carbon footprint of an AI server farm, they are often wearing a head-to-toe outfit made of polyester, nylon, and rayon. This is the plastic straw paradox: we are hyper-fixated on the visible, optional waste of the digital world while literally draping ourselves in the very petroleum products we claim to despise.

To understand the scale of this cognitive dissonance, we have to look at what synthetic fabric actually is. Polyester and nylon are plastic. Specifically, they are derived from petroleum and natural gas through an energy-intensive chemical process. If you were to walk into a coffee shop and throw a handful of plastic spoons into the ocean, you would be a social pariah. Yet, every time a polyester sweater is tumbled in a washing machine, it sheds hundreds of thousands of microplastic fibers—invisible, indestructible shards of plastic that bypass filtration systems and head straight for our waterways. These microplastics enter the food chain, working their way from plankton to the very people who bought the paper straw.

The environmental weight of a single-use plastic bag or a straw is a rounding error compared to the lifecycle of a synthetic garment. Producing a single polyester shirt emits significantly more CO2 than the electricity required to generate thousands of AI images. Furthermore, the garment industry is responsible for nearly 10% of all global carbon emissions—more than all international flights (2%) and maritime shipping (3%) combined. While data centers are increasingly criticized for their energy draw, they have a unique advantage: they can be, and often are, powered by a greening grid. You can run a GPU on solar or wind power, but you cannot decarbonize the physical molecules of a petroleum-based nylon jacket. Once that plastic is woven into a thread, it is a permanent carbon debt.

However, the ethics of AI go beyond just being less bad than the fashion industry. Digital creation is actively preventing the generation of physical trash through virtual prototyping. Before the advent of generative design and high-fidelity AI simulations, creating a new product—whether a car part, a shoe, or a piece of furniture—required dozens of physical prototypes. Those models were made of clay, foam, plastic, and metal, most of which ended up in a dumpster after a single test. Today, an engineer or designer can run 10,000 virtual stress tests on a digital model to make it 40% lighter and use 30% less raw material before a single physical object is ever manufactured. In this light, a few hours of GPU time is a massive net gain for the planet; it is the energy we spend to ensure we don’t waste the earth’s finite physical resources.

This brings us back to the perceived optionality of AI. The critic argues that a digital image is a luxury we don’t need, whereas a sweater is a necessity. But in the era of fast fashion, that sweater is rarely a necessity; it is a disposable trend designed to last a single season before joining the mountains of textile waste currently clogging the deserts of Chile and the beaches of Ghana. When we compare the carbon and plastic footprint of a digital creator using a server to the footprint of a consumer buying a cheap synthetic outfit, the math is staggering. The creator uses energy to move bits and optimize designs; the consumer uses oil to create a permanent, non-biodegradable object that will shed toxins into the environment for the next five centuries.

If we are to have a serious conversation about the ethics of environmental impact, we must move beyond the easy targets. It is easy to point at a large building full of flashing lights and call it a villain. It is much harder to look at our own reflection and acknowledge that our physical lifestyle—our synthetic clothes, our global shipping dependencies, and our addiction to disposable goods—is the true engine of ecological decline. The person railing against the data center while wearing a polyester blend isn’t just missing the point; they are the point. They are clutching a paper straw while standing in a house built of plastic, shouting at a mirror they don’t recognize.

Why Every Remix is a Lesson

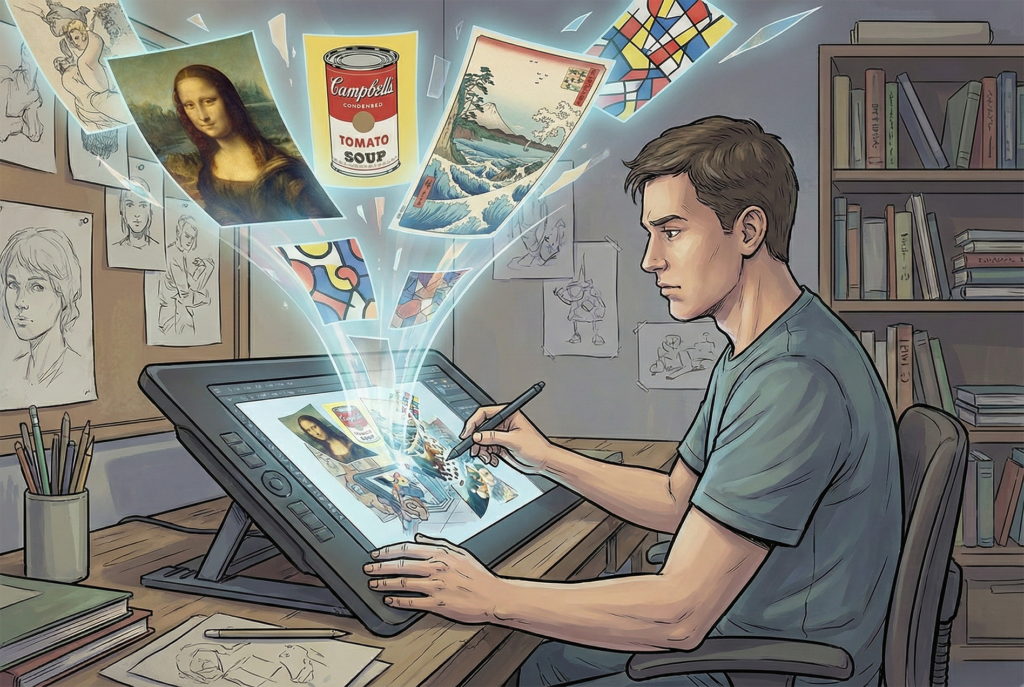

In the heated debate over AI-generated art, the word theft is used with the frequency and force of a gavel. The prevailing narrative suggests that these models are essentially digital scrapbooks, surreptitiously cutting out pieces of existing artwork and pasting them together to create a counterfeit whole. It is a compelling argument because it appeals to our innate sense of fairness—the idea that something cannot come from nothing. But this perspective fundamentally misunderstands both the architecture of the machine and the history of human creativity. As Austin Kleon argued in Steal Like An Artist, and as the documentary series Everything Is A Remix illustrated, no piece of art is truly original. Every creator is a composite of their influences, and AI is simply the first tool that makes that synthesis visible at the speed of light.

To understand why AI is not stealing, we have to look at what is actually happening inside the weights of a neural network. An AI model does not contain a database of images. It contains a mathematical representation of concepts. When it learns from a million photos of a sunset, it isn’t memorizing pixels; it is learning the relationship between a specific frequency of orange and the horizon line. It is learning the grammar of light. This is indistinguishable from the process an art student undergoes when they spend a weekend at the Louvre sketching the works of the Old Masters. We call the student inspired and we call the AI a thief, yet both are performing the exact same task: observing patterns in the world and internalizing the rules that govern them so they can apply those rules to something new.

While the debate over corporate data-scraping and consent is a legitimate legal hurdle for the industry to clear, it should not cloud our understanding of the tool’s creative function. AI is effectively a way to compress human knowledge. It is the first technology in history to democratize the act of visual creation by decoupling it from physical labor. For over a century, the barrier to entry for visual art was fine motor skills. If you had a tremor, a physical disability, or were neurodivergent in a way that made traditional hand-eye coordination impossible, you were effectively locked out of the category of artist. AI turns language into a brush. It allows a person with quadriplegia to iterate on a visual concept with the same nuance and visionary direction as a master painter. This is not a devaluing of art; it is an ethical triumph that allows the human spirit to bypass the limitations of the human body.

This is where the distinction between pattern recognition and plagiarism becomes vital. Plagiarism is the act of passing off someone else’s specific work as your own. Pattern recognition is the act of understanding how a work functions so you can create something in that same vein. If an AI generates an image that is a pixel-for-pixel replica of a living artist’s work, that is a failure of the model and a legitimate case of infringement. But if an AI generates an image that captures the aesthetic memory of an entire era—the lighting of a 1970s sci-fi cover or the brushwork of a Renaissance master—it is doing what humans have done for millennia. It is utilizing the collective memory of our culture to provide a new palette for expression.

The theft argument is often a proxy for a deeper fear: the fear that if the process of learning and synthesizing is automated, the soul of the work disappears. But the soul of art has never been in the mechanical act of learning how to draw a straight line or shade a sphere. The soul is in the choice—the decision to use a specific influence to provoke a specific response. By focusing on stealing, we are fixating on the ingredients of the meal while ignoring the chef who decided to put them together. AI is a vast, digital pantry of every flavor ever tasted; the ethics of the meal still depend entirely on who is standing at the stove.

Why Clicking the Button Isn’t the “Art”

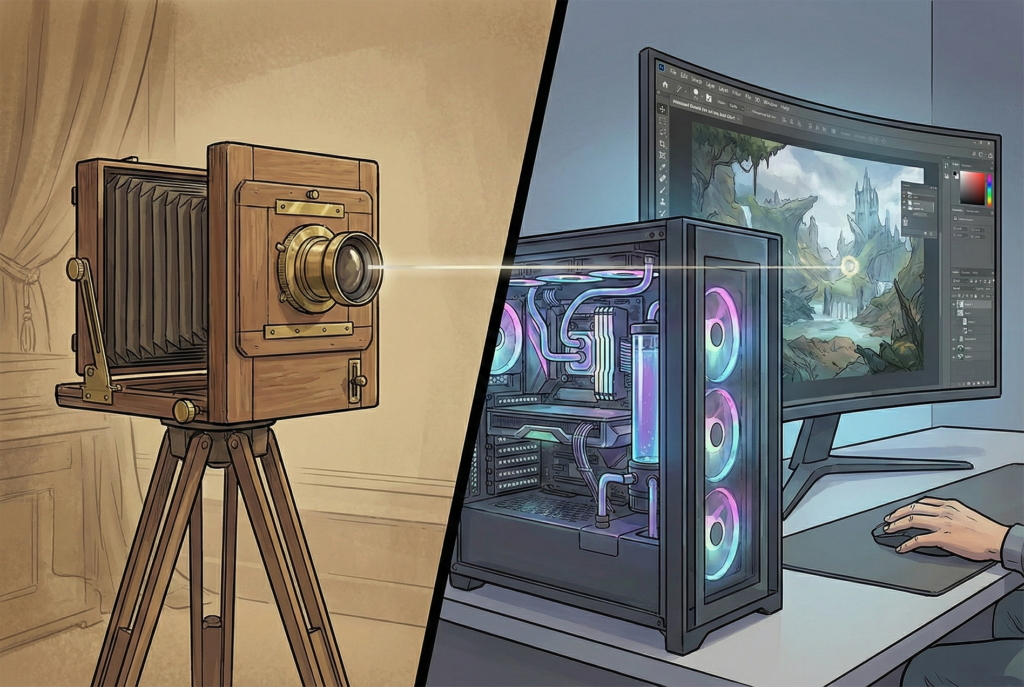

History has a funny way of repeating itself, especially when it comes to our fear of new buttons. In 1888, George Eastman released the Kodak No. 1 with a slogan that terrified the art establishment: “You press the button, we do the rest.” Suddenly, the ability to capture a likeness—a skill that had previously required decades of training in oils, pigments, and anatomy—was available to anyone with a few dollars and a steady hand. The cry from the painting community was immediate and apocalyptic. Paul Delaroche, a prominent French painter, is famously said to have declared that from that day, painting was dead. The logic was simple: if a machine can do the labor, the art must be gone.

Yet, over a century later, we don’t look at a grainy vacation photo from 1904 and a portrait by John Singer Sargent and struggle to tell which one is art. This is the core of the snapshot fallacy, and it is exactly where we find ourselves today with AI. Just as the camera didn’t kill painting—it merely forced it to stop obsessing over realism and move toward Impressionism and Cubism—AI isn’t killing art. It is simply automating the manual execution of the image, forcing the human creator to double down on what Marshall McLuhan called the character of the medium.

When McLuhan famously stated that the medium is the message, he wasn’t saying that the content doesn’t matter. He was arguing that the technology itself introduces a change of scale, pace, or pattern into human affairs. The message of the camera wasn’t the photographs it produced; it was the way it transformed our relationship with time and memory. Similarly, the message of AI isn’t the millions of cyberpunk cats being generated every hour. The message is the transition from art as a feat of manual labor to art as a feat of curation and intentionality.

Anyone can take a snapshot on their phone today, but that doesn’t make them a photographer. A snapshot is a reaction to an external stimulus—looking at a pretty sunset—whereas art is the result of an internal vision. Art is the juxtaposition of the unexpected. An artist using AI doesn’t just type a prompt and walk away; they iterate, they refine, and they apply an understanding of composition, the psychology of color, and historical context. They use the AI to explore conceptual boundaries that a layperson wouldn’t even know existed. In the hands of a master, AI is a workshop of digital assistants allowing for complex, symbolic storytelling that was previously gated by the sheer hours required for manual rendering.

This distinction is most visible in software engineering. A hobbyist can use an AI to generate a working “Hello World” program, but that doesn’t make them a senior development engineer. The senior engineer brings domain knowledge to the table. They understand architecture, edge cases, security implications, and long-term maintainability. The AI is their assistant, handling the grunt work of syntax so the expert can focus on the high-level logic that actually solves the problem.

For the artist and the knowledge worker, this should be an empowering realization, not a threat. We are moving away from a world where we pay for the time it took to draw a line, and toward a world where we pay for the wisdom of where the line was placed. If an artist uses AI and produces something with no merit, that isn’t a failure of the technology; it is a failure of their own creative intent.

The call to action for the modern creative is clear: stop charging for your labor and start charging for your vision. Michelangelo didn’t personally carve every square inch of his masterpieces; he directed a workshop of skilled hands to realize his vision. AI is simply the latest, most efficient workshop ever built. When a creative mind uses this tool to bridge the gap between a complex internal vision and a final image, they aren’t cheating the process. They are mastering the medium.

A Manifesto for the AI Era: Be a Visionary

When we step back from the frantic headlines and the social media skirmishes, a clearer picture of the AI landscape begins to emerge. It is not the dystopian wasteland of environmental collapse and creative bankruptcy so often described. Instead, it is a complex, high-speed evolution of the same tools we have been using since the first human blew pigment over their hand onto a cave wall. To call AI unethical is to ignore the far more damaging, invisible systems we support every day. It is a selective moralism that prizes the familiar over the efficient, and the physical over the digital, regardless of the actual cost to the planet or the soul.

The ethical defense of AI rests on a foundation of active optimization. As we have seen, the environmental water consumption of a data center is a manageable, closed-loop cycle of heat and water, a whisper compared to the toxic, petroleum-soaked scream of the global textile industry. But we must go further than mere comparison. AI is not just a lesser evil; it is the primary engine we will use to dismantle the greater ones. We are currently using this compute power to design the next generation of carbon-capture technology, to create hyper-efficient logistics that reduce global shipping waste, and to develop new materials that could one day replace the very plastics we currently drape over our bodies. To reject the energy cost of AI is to reject the high-speed calculator we need to solve the climate crisis.

Similarly, the accusation of theft falls apart when subjected to the light of creative history. AI does not steal; it synthesizes. It performs the same pattern recognition that every artist, musician, and writer has performed for millennia, only it does so with a broader library and a faster processor. By democratizing the ability to transform language into vision, AI isn’t devaluing art—it is expanding the definition of who can be an artist. It removes the physical tax of fine motor skills and replaces it with a premium on intentionality and concept. It allows the visionary to lead, rather than just the laborer. This is an empowering shift for any knowledge worker. For centuries, artists and engineers have been paid for the manual execution of their tasks. Today, the market for execution is being commoditized, which means the market for vision is becoming more exclusive and more valuable.

This brings us to the future of work and the role of the expert. Just as the camera didn’t replace the painter and the calculator didn’t replace the mathematician, AI will not replace the artist or the engineer. It will, however, replace the tedium that once defined their days. Domain knowledge remains the ultimate filter. A senior engineer or a master artist uses AI as leverage—a way to amplify their expertise and skip the boilerplate to get to the heart of the problem. Those who fear being replaced by the machine are often those who have confused their value with their output. The output is now cheap; the vision is more expensive than ever.

Ultimately, the ethics of AI are not found in the code or the cooling towers, but in the hands of the user. In the hands of a lazy person, AI creates noise; in the hands of an artist, it creates meaning. As we move further into this era, the most ethical thing we can do is to stop fighting the medium and start mastering the message. We must demand sustainability from our tech, honesty from our influences, and excellence from ourselves. If we devalue ourselves by claiming that a machine can do what we do, we are admitting that our contribution was merely mechanical. But if we recognize that our value lies in our taste, our experience, and our ability to bridge the gap between the expected and the profound, then AI becomes the greatest brush we have ever held.

AI is not the end of our story—it is the most powerful mirror we have ever built, and it is time we stopped being afraid of what we see in it.