The Un-Romantic Truth About Lasting Love: It’s All About Structure

We’ve all been fed a steady diet of cinematic romance since we were old enough to hold a remote. You know the drill: the rain-soaked declaration of love, the perfectly timed airport chase to stop the plane, the boombox held aloft outside a bedroom window in an act of defiant devotion. We grow up conditioned to believe that the glue holding a relationship together is composed of grand gestures, earth-shattering sexual chemistry, and a photographic memory for anniversaries.

And don’t get me wrong, those things are lovely. Who doesn’t want a little movie magic in their life? But if you’ve ever tried to build a life with another distinct, complicated human being for longer than the running time of a rom-com, you know the truth. The boombox eventually runs out of batteries, the rain stops, and you’re still left standing in the kitchen at 7 p.m. on a Tuesday arguing about whose turn it is to empty the dishwasher.

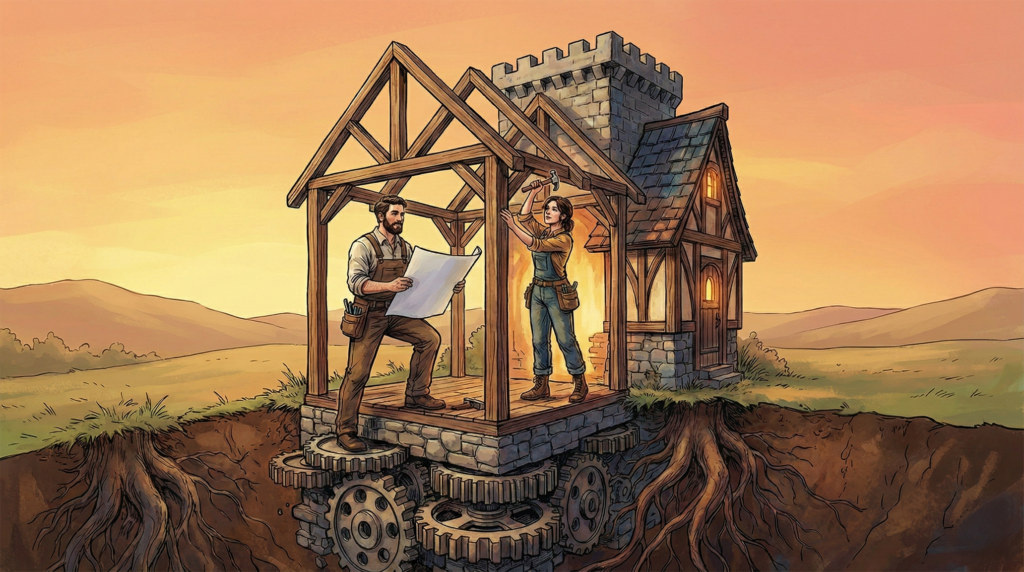

The reality is that the structural integrity of a long-term relationship—the stuff that keeps it standing through life’s hurricanes and its mundane doldrums alike—is surprisingly un-cinematic. It’s less about fireworks and more about foundation repair. The things that truly make a relationship work are infinitely more durable than just tender moments.

If you strip away the Hollywood sheen, the core components that actually build a lasting connection are shockingly practical. They are: Emotional Vulnerability, Structural Interdependence, and Future Certainty.

Sounds a bit dry, doesn’t it? Like something you’d find in an architectural manual rather than a love letter. Structural interdependence isn’t exactly a phrase that gets the heart racing when whispered over a candlelit dinner. Yet, these three concepts are the bedrock upon which real trust, deep intimacy, and resilient partnership are built. Without them, all the romance in the world is just a pretty facade waiting for the first strong wind to knock it down.

In this deep-dive essay, we’re going to trade the rose-colored glasses for a magnifying glass. We’ll explore what it really means to be emotionally vulnerable without feeling unsafe. We’ll look at how the unsexy business of merging lives and resources is actually a profound act of intimacy. And we’ll examine why simply knowing your partner isn’t going anywhere is perhaps the most romantic thing of all. Along the way, we’ll call on some familiar characters from literature who navigated these waters (some successfully, some disastrously), back our claims with psychological insights, and try not to take ourselves too seriously. Because let’s face it, love is serious business, but that doesn’t mean we can’t have a little fun figuring it out.

Part I: The Naked Truth—Emotional Vulnerability

If structural interdependence is the bones of a relationship, then emotional vulnerability is its nervous system. It is the part of us that is incredibly sensitive, prone to getting its feelings hurt, and—unfortunately for those of us who prefer to keep our metaphorical armor polished and impenetrable—absolutely essential for a real connection.

Brené Brown, the researcher who basically became the patron saint of vulnerability, defines it as “uncertainty, risk, and emotional exposure.” In a relationship, this translates to the terrifying act of letting someone see the parts of you that aren’t curated for Instagram. It’s the willingness to say, “I’m scared I’m failing at my job,” or “It really hurts my feelings when you use that tone,” rather than retreating into the safe, chilly fortress of “I’m fine.”

The Ogre Layer of Intimacy

Think of Shrek, not just for the meme, but for the philosophy. “Ogres are like onions,” he famously tells Donkey. “Layers. Onions have layers.” Human vulnerability is exactly the same. The outer layer is the social self: the witty, competent person who knows which wine to order. But as you peel back the layers, things get a bit more… pungent.

True emotional vulnerability is the act of handing someone the knife and trusting them not to slice the onion too thin. It’s the deepest fears part of the equation. We aren’t talking about a fear of spiders; we’re talking about the core-wound stuff. The fear that we are fundamentally unlovable, or the fear that we will eventually be abandoned just like we were in the third grade.

In literature, we see this played out most poignantly in the relationship between Elizabeth Bennet and Mr. Darcy in Pride and Prejudice. For the first half of the book, they are both wearing heavy suits of social armor. Darcy is haughty and fastidious; Elizabeth is prejudiced and defensive. It is only when they both experience the ego-shattering pain of vulnerability—Darcy through a humiliatingly rejected proposal and Elizabeth through the realization of her own errors—that a real connection becomes possible. They had to stop being correct to start being close.

Why It’s Actually Hard (and Slightly Gross)

Let’s be honest: vulnerability feels gross while you’re doing it. It’s the sweaty-palm, lump-in-your-throat sensation of saying something that could be used against you. Evolutionarily speaking, we are wired to hide our weaknesses. If you were a prehistoric human and you told the tribe, “Hey guys, I’m feeling really insecure about my mammoth-hunting skills,” you might find yourself left behind when the tigers show up.

But in a modern relationship, the mammoth is the distance between two people. According to the Gottman Institute, a leading authority on relationship stability, the ability to make and receive bids for connection is the primary predictor of success. A bid can be a sigh, a touch, or a confession. Vulnerability is the ultimate bid. It says, “I am opening a door; please don’t slam it.”

When we refuse to be vulnerable, we engage in what psychologists call stonewalling or masking. We become a flat, two-dimensional version of ourselves. You can’t truly love a statue, and you certainly can’t build a life with one. As the poet Khalil Gibran wrote, “Love gives naught but itself and takes naught but from itself… To love is to be vulnerable.”

The Power of the Ugly Cry

There is a specific kind of intimacy that only exists on the other side of a total emotional breakdown. You know the one: the ugly cry where your nose is running, your face is blotchy, and you’re saying things that make no logical sense.

In that moment, your partner has a choice. They can treat you like a logical puzzle to be solved (which, hint, I speak from experience when I say this never works), or they can meet you in the trenches. Supporting a partner in their vulnerability creates a neurological feedback loop. When we reveal a fear and receive empathy instead of judgment, our brains release oxytocin—the “bonding hormone.” It tells our nervous system, “This person is a safe harbor.”

C.S. Lewis hit the nail on the head. The alternative to vulnerability isn’t strength; it’s a very lonely kind of safety.

“To love at all is to be vulnerable. Love anything and your heart will be wrung and possibly broken. If you want to make sure of keeping it intact you must give it to no one, not even an animal… It will not be broken; it will become unbreakable, impenetrable, irredeemable.”

C.S. Lewis

Putting it into Practice (Without the Melodrama)

You don’t have to confess your darkest secrets every night over dinner to be vulnerable. Sometimes, it’s just about being honest about your needs. Let’s consider two different approaches, we’ll call them vulnerability lite, and deep diving.

The vulnerability lite approach looks like “I’m having a really hard day and I just need you to tell me I’m doing a good job.” The deep dive would say “When you don’t answer my texts for five hours, I start to feel like I’m not a priority, and it triggers that old feeling of being overlooked.”

The first one is a request for support; the second is a revelation of a wound. Both require the courage to admit that you aren’t a self-sustaining island.

In the end, emotional vulnerability is the price of admission for intimacy. You can’t have the us-against-the-world feeling if you’re still keeping part of yourself hidden away. It’s about taking the safety net away and realizing that, surprisingly, the fall isn’t what kills you—it’s the silence.

Part II: The Logistics of Love—Structural Interdependence

If emotional vulnerability is the nervous system, structural interdependence is the skeleton. And let’s be honest: skeletons aren’t particularly sexy. No one writes a sonnet about a shared Google Calendar or the sublime beauty of being listed as an authorized user on a credit card. Yet, in the architecture of a long-term relationship, these are the load-bearing walls.

Structural interdependence is the process of weaving two separate lives into a single, functional tapestry. It’s the merging of resources, the cohabitation of space, and the messy, often boring reality of becoming mutual emergency contacts. In the modern dating world of keeping things casual and maintaining independence, the idea of interdependence can feel a bit like a trap. But in reality, it is the highest form of commitment.

The All-In Philosophy

To understand structural interdependence, we have to look at the difference between a contract and a covenant. A contract is “I will do this if you do that.” It’s a transaction. A covenant (the stuff of interdependence) is “We are doing this together, and our fates are now linked.”

When you move in together, merge finances, or buy a dog that neither of you can reasonably care for alone, you are creating exit costs. In the cold, hard language of economics, this sounds terrifying—like a trap. But in the architecture of a life, it’s more like a mortgage on a house you love. Yes, a mortgage traps you to a property, but it also provides the equity and stability that a month-to-month lease never could.

You aren’t staying because you can’t leave; you’re staying because you’ve built something so specifically suited to you that the cost of dismantling it is high—and that’s a good thing. It means that when you have a spectacular argument about the dishwasher, you don’t just walk out the door. You stay and fix the foundation because the “house” is too valuable to abandon over a stray fork.

In literature, few partnerships embody the grit of structural interdependence like Sherlock Holmes and Dr. John Watson. While not a romantic couple in the traditional sense, they are the gold standard for functional interdependence. Their bond isn’t held together by shared sentimentality, but by the complex, interlocking machinery of their lives at 221B Baker Street.

Holmes provides the erratic, brilliant fire of deduction, but he is a man who would likely forget to eat or pay the rent without Watson’s grounding influence. Watson, conversely, provides the medical expertise, the moral compass, and the essential human interface for a world Holmes often finds baffling. They don’t just share a lease; they share a specialized ecosystem. Their survival—and their success—is a collaborative project. While we don’t usually have to solve London’s most baffling murders, the principle remains: a relationship is a small, two-person economy where each partner manages a vital department that the other cannot.

The Safety of Shared Resources

There is a psychological shift that happens when you stop saying my money and your money and start saying our budget. It signals a move from a competitive mindset to a collaborative one.

According to research published in the Journal of Consumer Research, couples who merge their finances tend to be happier and more likely to stay together. Why? Because it reduces the yours vs. mine friction and fosters a sense of shared goals. It’s an act of radical trust. You are essentially saying, “I trust you with the thing our society values most (capital) because I value us more.”

This interdependence extends to the mundane. Who picks up the dry cleaning? Who remembers that your mother-in-law is allergic to shellfish? Who is the one who handles the scary phone calls to the insurance company? This is what sociologists call cognitive labor. When you share this burden, you aren’t just roommates; you are a team. You become a super-organism that is more capable of handling the world than two individuals standing side-by-side. And yes, feeling like someone always has your back can lead to a super-orgasm (admit you read that in the previous sentence!).

The Emergency Contact Test

There is no greater romantic declaration than the moment you change your emergency contact from “Mom” to “Partner.”

Think about the character of Arthur Dent in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. He spends the entire book being tossed around the universe, utterly untethered. The horror of his situation isn’t just the destruction of Earth; it’s the total lack of structural interdependence. He has no one who has to look for him.

When you have structural interdependence, you have a designated person. If you end up in the hospital, they are the one the doctors talk to. If your car breaks down at 3 a.m. in a rainstorm, they are the one who has to get out of bed. It’s the in sickness and in health part of the vows, but applied to the flat tire of life.

The Humor in the Mundane

Let’s acknowledge the absurdity of it for a moment. We fall in love because of a spark, a laugh, or a shared passion for 90s grunge music. But we stay in love because we figured out a system for who buys the toilet paper.

As the writer Nora Ephron noted in her essays about domestic life, the little things are actually the big things. There is a strange, quiet intimacy in knowing exactly how your partner likes their coffee, or knowing that if you don’t buy the good butter, they’ll be slightly grumpy for the rest of the afternoon. These are the threads of interdependence. They aren’t glamorous, but they are the things that make a house a home.

“The strongest relationships are between two people who can live without each other but don’t want to. But the most functional relationships are between two people who have made it very, very difficult to leave.”

a very wise divorce lawyer

The Balance: Independence vs. Enmeshment

A quick warning: structural interdependence isn’t about losing your identity. It’s not about becoming a we so completely that the I disappears. That’s called enmeshment, and it’s a one-way ticket to resentment.

Healthy interdependence is like two trees planted next to each other. Their root systems are intertwined, sharing nutrients and stabilizing each other against the wind, but they still have their own trunks and their own branches reaching for the sun. You want to be mutually reliant, not mutually erased.

In the end, merging your life with someone else’s is an act of courage. It’s a bet that the future you build together will be better than the one you could build alone. It’s the realization that while you can do it all by yourself, you’d much rather have someone else to help you carry the groceries.

Part III: The Anchor of Peace—Future Certainty (Security)

If emotional vulnerability is the nervous system and structural interdependence is the skeleton, then future certainty—often called relational security—is the skin that protects the entire organism. It is the quiet, steady hum of knowing that the person sitting across from you today will still be there when the calendar flips to next year, the next decade, and the next mid-life crisis.

In a world that prizes keeping your options open and situationships, future certainty is the ultimate counter-culture movement. It is the reasonable expectation that the relationship will persist and that you will both be there for each other when the metaphorical (or literal) roof starts leaking. It’s the difference between a high-stakes poker game where you might lose everything on a bad hand and a long-term investment that you check once a year while sipping tea.

The Psychology of Safe Haven

To understand why we crave this so deeply, we have to look at attachment theory, the brainchild of John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth. They theorized that humans are biologically wired to seek a secure base. For a toddler, this looks like a parent who stays in the room while the child explores a new toy. For an adult, it looks like a partner who stays in your life while you explore a new career or navigate the loss of a parent.

When we have future certainty, our brains switch from survive mode to thrive mode. According to Dr. Sue Johnson, a pioneer in relationship science and developer of Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT), the fundamental question we are all asking our partners—whether we are three years old or eighty-three—is: “Are you there for me?” When the answer is a consistent, predictable “Yes,” something remarkable happens to our physiology. Our cortisol levels drop, our blood pressure stabilizes, and our prefrontal cortex—the part of the brain responsible for creativity and logic—can actually function. Without certainty, we are essentially living in a state of low-level fight or flight, perpetually scanning the horizon for signs that our partner is packing their bags.

The Lit-Check: Jane Eyre and the String of Connection

While many point to the grand, tragic romances of literature, the real lesson in future certainty comes from Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre. For the first half of the book, Jane is a woman untethered, drifting from one cold institution to another with zero certainty about her future. When she finally finds love with Mr. Rochester, the most famous description of their bond isn’t about passion—it’s about a literal, physical sense of security.

Rochester famously tells her, “I have a strange feeling with regard to you. As if I had a string somewhere under my left ribs, tightly and inextricably knotted to a similar string situated in the corresponding quarter of your little frame.” This metaphorical string is the essence of future certainty. It is the belief that even if they are physically apart, or even if the world is burning down (which, in the book, it quite literally does when Thornfield Hall catches fire), the connection is immutable. Jane’s journey ends not just with a wedding, but with the profound, quiet certainty of their final union, where she declares, “I am my husband’s life as fully as he is mine.” They didn’t just find a spark; they found an anchor.

The High Cost of the Situationship

The opposite of future certainty is relational ambiguity, and it is a neurological nightmare. In modern dating, we often avoid The Talk because we don’t want to seem clingy. But ambiguity is the ultimate thief of joy.

Research from the University of Virginia found that even the threat of a breakup significantly impairs a person’s ability to regulate their emotions. If you are constantly wondering, “Is this the week they realize they could do better?” you aren’t actually in a relationship; you’re in an extended job interview. And nobody is their best self during a job interview. You’re guarded, you’re performative, and you’re exhausted.

Future certainty allows you to stop interviewing. It’s the sweatpants of the soul. It provides the psychological safety required to be truly vulnerable (refer back to Part I). After all, why would you show someone your deepest fears if you think they might be gone by Tuesday?

The Humour of the Foregone Conclusion

There is a specific kind of comedy in being a foregone conclusion. It’s the stage of a relationship where you stop asking, “Do you want to go to my cousin’s wedding in six months?” and start saying, “We have that wedding in June, so don’t book anything.”

It sounds boring, but there is a hidden hilarity in the mundane certainty of a long-term partner. It’s knowing that you will be annoyed by their specific way of loading the dishwasher for the next forty years. It’s the realization that you have a designated person to hold the other end of the measuring tape until death do you part.

Returning to Nora Ephron, she once implied, the most romantic thing in the world isn’t a bouquet of roses; it’s a person who knows exactly how you take your coffee and has no intention of ever making it for anyone else. There is a profound, albeit unsexy, peace in knowing that the person who has seen you with the flu, at your most irrational, and during your most failed attempts at DIY home repair, has already decided that they aren’t going anywhere.

Security is a Launchpad, Not a Cage

One common misconception is that certainty equals stagnation. People fear that if they are too secure, they will stop trying, or that the relationship will become a prison of musts.

But the data suggests the opposite. This is known as the dependency paradox. The more securely attached we are to a partner—the more we can depend on them—the more independent and adventurous we actually become in the outside world. When you know you have a soft place to land, you’re willing to jump higher. You take that career risk, you speak your mind, and you grow as an individual because you aren’t constantly worried about your home base being dismantled while you’re away.

Future certainty isn’t about losing your freedom; it’s about gaining the freedom to be your full self without fear of abandonment. It is the realization that while you could survive alone, you have chosen to build a future where you don’t have to.

Conclusion: The Architecture of an Unshakable Us

We often treat love like a mystery—a capricious lightning bolt that strikes without warning and vanishes without reason. We spend our lives looking for the spark as if it’s the only thing that matters, forgetting that while a spark can start a fire, it takes a well-built fireplace to keep a home warm through a long winter.

The three pillars we’ve explored—emotional vulnerability, structural interdependence, and future certainty—are that fireplace. They aren’t the stuff of breathless, rain-soaked movie posters, but they are the stuff of 50th-anniversary parties. When you have all three, you aren’t just dating or seeing someone; you have constructed a fortress that can withstand the inevitable erosions of time, ego, and the occasional catastrophic argument about how to properly load the dishwasher.

The Synergy of the Three Pillars

These elements don’t exist in isolation; they are a mutually reinforcing trifecta. Think of them as a tripod:

- Vulnerability without security is a recipe for anxiety. You’re sharing your deepest self with someone who might not be there tomorrow.

- Interdependence without vulnerability is just a business arrangement. You’re roommates with a shared bank account but no soul.

- Security without interdependence is just a long-distance friendship. You know they’re there, but your lives aren’t actually touching.

When they click together, however, the result is what the Erich Fromm called the art of loving. In his seminal work, he noted that love is not a sentiment which can be easily indulged in by anyone, regardless of the level of maturity reached. It is a construction. It requires us to be brave when we want to be guarded, to be collaborative when we want to be selfish, and to be committed when the world offers us endless better options.

“Love is not something you find. Love is something you build.”

Adage

The Final Blueprint

As we’ve seen, from the strings of Jane Eyre to the teamwork of the Sherlock and Watson, lasting love is remarkably practical. It’s about being seen, being needed, and being around for. It’s the realization that you don’t have to perform anymore. You can be the messy version of yourself (vulnerability), you have a partner to help carry the groceries (interdependence), and you can sleep soundly knowing they’ll still be there in the morning (certainty).

So, the next time you find yourself stressing over whether your relationship is passionate enough or if the spark is as bright as it was on day one, take a step back and check your foundation. Are you still sharing the scary stuff? Are you building a life that is truly shared? Are you giving each other the gift of a certain future? If the answer is yes, then you’re doing the real work. The rest—the flowers, the sex, the anniversary dates—is just the decor on a very, very solid house.

Further Support

If you like my breakdown of relationships into these three components, you might find this checklist handy. It is designed to help you move from theory to practice. It’s less of a pass/fail exam and more of a diagnostic tool to see where your foundation is rock-solid and where you might need to do a little structural maintenance.

Pillar 1: The Vulnerability Pulse-Check

Emotional vulnerability is about the inside stuff. It’s the metric of how much of your true self is actually present in the room.

- The Weird Fear Test: Could you tell your partner about a deep-seated insecurity (e.g., “I’m worried I’m becoming my father”) without fear of judgment or mockery?

- The Masking Frequency: How often do you feel the need to perform or clean up your emotions before showing them to your partner?

- The Bid Response: When you reach out for connection (a sigh, a look, a comment about your day), does your partner generally turn toward you with interest?

- The Conflict Style: During an argument, do you eventually move toward This is why I’m hurting (vulnerable) rather than staying in This is why you’re wrong (defensive)?

Pillar 2: The Interdependence Audit

Structural interdependence is about the logistics of us. It’s the metric of how effectively you’ve merged your tactical lives.

- The Emergency Contact Factor: If you were in an accident, is your partner the first person called? Do they know your medical history, your insurance, and where the spare key is?

- Financial Synergy: Regardless of whether you have shared or separate accounts, do you have a unified plan for money that both of you understand and agree on?

- The Cognitive Load: Is the mental labor of the household (bills, social calendars, chores) shared in a way that feels like a partnership rather than a manager/employee dynamic?

- Exit Costs: If the relationship ended tomorrow, would the unraveling be complex? (Surprisingly, the more entwined you are, the more stability you often have during rough patches).

Pillar 3: The Certainty Survey

Future certainty is about the anchor. It’s the metric of how safe you feel to be yourself because you know the other person isn’t leaving.

- The Five-Year Horizon: When you think about your life five years from now, is your partner a default, unquestioned fixture in that vision?

- The Fight Aftermath: After a major disagreement, is your primary fear We are going to break up, or is it We have some work to do to fix this?

- The Sweatpants Comfort: Do you feel the psychological safety to be your least attractive or least productive self without fearing that your value in the relationship has dropped?

- The Reliability Quotient: Does your partner’s history of behavior suggest that they will show up for you in a crisis, even if it’s inconvenient for them?

How to Use This

If you found yourself nodding through two sections but feeling a bit iffy on the third, that’s your starting point. Relationships rarely have all three pillars at 100% capacity all the time. The goal is to ensure the tripod is balanced enough to hold the weight of your shared life.

As you look over these, remember that perfect is the enemy of sturdy. You don’t need a flawless foundation; you just need one that you both trust enough to keep building on.